This Was Not in the Brochure

Alum News

In her one-woman show, Phoebe Potts ’92 proves that laughter can be an antidote to the emotional highs and lows of the adoption process

Published July 16, 2025

Phoebe Potts ’92’s award-winning one-woman show, Too Fat for China: A Comic Look at the Agony of Adoption, chronicles her and her husband’s quest to adopt a child. It’s not normally a comedic topic, but by sharing her unique perspective Potts takes audiences on a riotously funny journey while also offering some serious commentary on the moral and ethical issues related to adoption and its often corrupt commercial side.

“Part of the story of Too Fat for China came from wondering why do I get to be a person who adopts and why does a birth mother have to place her child for adoption. No one thinks about the experience of this other person,” she says. “It became very clear that adoption is a business, and businesses are about making money. Inherent in it is this lie that it is supposed to be about bringing families together. And I was complicit in the lie. That didn’t sit well with me—but I really wanted the kid.”

The title of her show came to Potts after she discovered that China requires potential adoptive parents to have a Body Mass Index (BMI) of less than 29. Potts is quick to confess that her BMI is a tad over that level and, thus, she’s considered too fat to legally adopt a baby from China. Plus, adoptive parents cannot be on antidepressants, which she freely admits to taking—though she notes, somewhat ironically, that many antidepressants are produced in China. In her show, she jokes, “What do they think we’re doing with all these antidepressants if not parenting?”

Too Fat for China, which debuted in Potts’ hometown of Gloucester, Massachusetts, in 2019, is the sequel to Potts’ 2010 graphic novel, Good Eggs, which dealt with her fertility treatments and unsuccessful pregnancies—an unusual topic for a graphic novel at the time, though it made perfect sense to Potts. “I was always drawing cartoons for my family about what was happening, but mostly drawing them for myself about situations I couldn’t control,” she says. “But, I could control the narrative, if I drew it.” Despite high praise, Good Eggs didn’t sell well, which was one reason publishers passed on Too Fat for China. Ever resourceful, Potts turned her book into a performance piece, bringing her humor, honesty, and sharp personal insights to the stage. “Part of the reason I did comics is because I not only wanted to tell people stories, I also wanted to show them,” Potts says. “Telling the stories from the stage was catnip to me.”

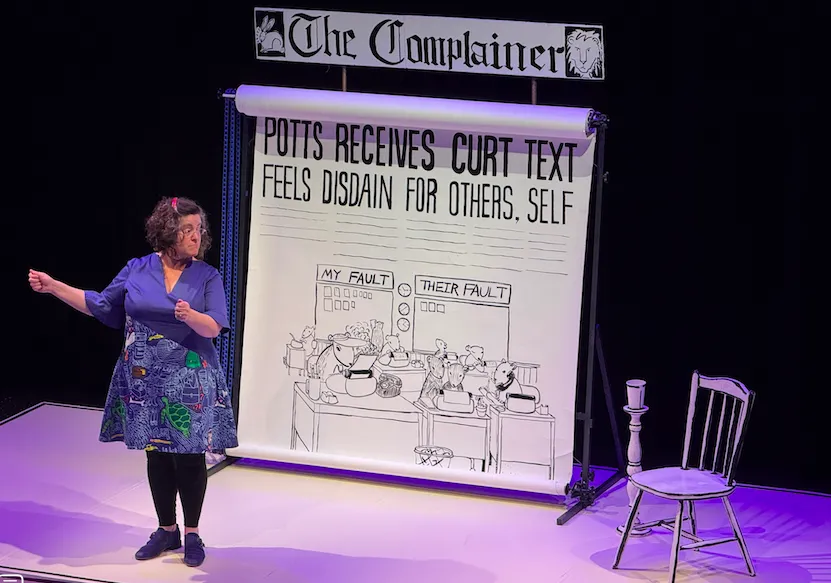

Her illustrations are a key component of the production. Throughout the show, Potts yanks on a chain pulley—or what she refers to as a life-size “crankie”—to scroll through a series of her cartoon-like drawings, all of which help illuminate her storytelling. “I’d always loved Torahs, the way they go side to side and they scroll,” says Potts, when explaining how she settled on the contraption, “and since the 1700s, people have drawn pictures on spools and turned them as they’re telling a story for a group of people.”

Potts on stage during a performance of Too Fat for China.

Potts’ knack for storytelling developed at a young age. Her parents, both journalists, instilled in her a love for a good yarn. “If you wanted the warm sunshine of their love, you couldn’t just be like, ‘How was your day?’ ‘Fine.’ No. You had better tell a good story,” she recalls. Her Jewish faith was also formative. “The thing that has bound the Jewish people together forever is stories,” Potts says.

At Smith, Potts majored in history and then earned a master’s in studio art and art theory from Maine College of Art. After graduating, she worked as a union organizer (as a Smith student she supported dining services staff during a round of staff reductions and eventually joined workers and other students to form the United Student Employee Delegation) and later led a family learning program at her local synagogue. “I would get kids and adults to read a piece of text and figure out ways for them to inhabit it through drama, video, comic strips—anything to make it more meaningful,” she says. Her husband, Jeff Marshall, teaches art at North Shore Community College. And—spoiler alert—their son, Lemi, whom they adopted as a baby from Ethiopia, is now 15 years old.

Last year, Potts was a writer in residence at Endicott College, where she taught a class on writing about life challenges. In class, Potts often refers to artists who have used heartbreak as a catalyst for their work. (“Look at Taylor Swift.”) But for her the art of storytelling and performance goes deeper than just an emotional exorcism. “The thing that powers me to tell these stories is I want to get to the truth of what’s really going on,” she says.

One unfortunate truth she discovered was that the rights of mothers and babies are not well protected. Rather, in many cases, finances take precedence over everything else. For example, some agencies and organizations group adoptive parents by financial resources. “When we first started looking into domestic adoption, we only had $26,000 to fund the process,” says Potts. “We learned from three different agencies (all in New England) that adopting a baby would cost $40,000, but if we were ‘open to race,’ we could get a Black baby girl for $28,000 and Black baby boy for $24,000. These programs had noxious names like ‘rainbow stork’.”

What helped Potts manage the stress and anxiety of the process was connecting with other adoptive parents. She remains involved with several social media groups for adoptive parents and is very supportive of the trend to highlight the voices of adult adoptees. “It turns out what adoptees need—among many other things—is to know other adoptees,” she says. “They need to know people who have this unique experience of being cut off from the first family and then sort of grafted onto another family. The way that story has been told until now is how wonderful that this family came together without acknowledging the loss in the first family. What lasting effects does that have?”

One of the ways Potts has tried to honor her son’s birthplace is by joining him in taking online Amharic lessons with a woman in Ethiopia. Amharic, the official working language of Ethiopia, is also a Semitic language and is, in many ways, close to Hebrew. “There’s this overlap to the tradition that he was raised in,” says Potts.

Too Fat for China, which won the Best Storytelling award at the United Solo Theater Festival in 2023, is touring across the country for the rest of the year, and Potts is already working on new material. She hopes that her one-woman shows will be available on a streaming service at some point, but performing live will always be a passion. “It’s the opposite of the internet,” she says. “On the internet, everybody is looking at the same thing, separately, and it’s on repeat. Whereas live theater is this one moment, where we’re all around the fire, like in our early days of existence. That is incredibly nourishing for me as an artist, but also allows me to walk with my head held high as a human being.”